Folklore

Stories from the area 18th and 19th Century, from the Duchas.ie Folklore project.

Old Schools

In 1794 there was an old school in St Mullins in the middle of the graveyard and part of it is still standing. Every night about thirty boys used to gather into the school and were taught by a lay teacher or a priest.

The pupils were taught Latin, Greek, arithmetic and French. They used to sit on stones, and write on slates, and the teacher used to write on a big flag. There was a small hole through the wall and the teacher could get a clear view of the moats, on which the boys took their turns for watching and if they saw the yeomen coming they signalled to the master, and he and his pupils would fly. The teacher it is believed was a local man, and some say his name was Doyle. Folklore, 1937, Martin Carroll b. 1883 Duchas >

In 1775 there was a hedge school in Ballyknock, St Mullins, Co Carlow. It was held in Doyle’s field beside Ballyknock lane. They had no house to go into when it would rain. The teacher’s name is not known as he was a stranger. He was paid a weekly wages and he lodged at Rourke’s. He taught Irish, English and Latin to his pupils. They spoke the Irish language mostly and did most of the subjects in Irish. They had no pens nor copies. They wrote on slates with slate pencils. They had no seats to sit on but stood in classes around the teacher and had no blackboards. Told by Patrick Murphy, Bauck, St. Mullins >

In days gone by there were no fine schools like we have now. They were only built by putting sticks up against the ditch and covering them over with boughs. There were a few of those old schools in this district. There was one in Ballyknock in Thomas Rourke’s land, but at that time it was owned by the Morissey family of Drana. The school was built about the place that Miss Kate Cleare is living. Those old schools were known as hedge schools and were mostly taught at night. The pupils were not supplied with a fine fire as they are now, but each one had to bring a sod of turf as that was the only fuel they had those days. In other cases they taught school in the farmers’ houses. Folklore 1937 >

Local marriage customs

When people are going to get married in our county the neighbours say “the match is made and all”. “All” means that a lot of work and talk and arrangements have been done before hand. Before the match is made if the bride is marrying into a place her father and a friend go to this place to make sure that it is suitable and to “walk the land” This is because the bride has to bring a fortune to her future husband. The favourite time for marriages in our district is the period from Christmas to Shrove Tuesday usually called “Shraft”. The wedding feast is always held at the bride’s house. Honeymoons are very rare, so the new husband and wife go to their future home the same day as the marriage when they are visited by a crowd of strawboys. Ballinacoola, St. Mullins Folkore >

Shrove is the principal time of the year that marriages take place and especially on Shrove Tuesday.

Wednesday is the luckiest day to get married and the lucky colour is blue. Matches are made in this district. The intended bridegroom goes to the house of the bride to be, and brings another man with him. They bargain for a certain amount of money. If the bride’s father has not the required sum he makes it up with cows or sheep. The day for the marriage is fixed. The people were married in their own house up to 1877. The priest went to the houses and performed the ceremony. The priest cut the wedding cake and all the guests put silver on the plate for him. At night the cailleacs come and are welcomed. They wear a mask on their faces and are dressed up with old clothes and carry big sticks. Some of the cailleacs bring a musical instrument and start to dance when they arrive and enjoy themselves until the early hours of the morning. Folklore. Drummin, St. Mullins, Co. Carlow.

In old times there were strange marriage customs. Marriages were performed at night at the house of the bride There was great fun all night, dancing singing, and feasting. Then the strawboys would go to the houses where the wedding was held. They would look very funny with different dresses and their faces covered with masks. Some of them would cause great trouble if they were not treated with kindness. The hauling home took place a month after marriage. They would have a great dance again The strawboys would come that night too. Men brought home their wives on horse back behind them. Shrove tide is the time that marriages most frequently take place. Folklore. Ballynalour, St. Mullins, Co. Carlow. >

In olden times the people believed that Wednesday was the best day for getting married and that December was the luckiest month. The people would go to the chapel on horse back and the pair who were to be married would go on the one horse. On the night of the wedding strawboys or “coilleacs” would go to the house of the boy who was married and from that to the bride’s house. When coming from the church the people who attended raced home to see who would win and then they believed that the winner would be the next to be married. When the coilleacs went to the house that night they were dressed with red coats, navy blue trousers and paper hats. They had paper or cloth over their faces to disguise themselves. Michael Doyle, Poulmounty, St. Mullins >

Mass in the Penal Days

In the Penal days when people were forbidden by the English to say Mass they had to go out and say Mass under an oak tree or in other hiding places. In St Mullins many years ago a priest used to say Mass in the graveyard. A little stone altar can be seen quite plainly yet. Around this altar was a hole about six or seven feet down in the ground. In this the people used to hear Mass. Just outside the cemetery stands the Moat and on the top of it while the priest was saying Mass a few people used to watch and when they would see the soldiers coming they would let a shout and the priest and the people would hide. >

In 1798 mass used to be celebrated secretly at the back of the blessed well in St Mullins. Every night about twelve oclock many people could be seen going through the fields to escape being seen. One dark night they set out to hear mass and stealing along behind them was an informer. “Blackleg” Staunton was his name. When he saw where the people were going he slipped back into a field now called the Raheen and lit a lantern. He flashed the light three times and the soldiers watching knew what it meant. Quickly they came and the informer showed them where mass was being said. The soldiers came down on the people and slaughtered every one of them. The priest alone escaped. Martin Carroll, St. Mullins 1937 >

The Penal times were very hard round this district The priests in St Mullins had to hide themselves while saying mass. The soldiers would kill them if they caught them and would sell them. There were people called priest hunters who went through the country, and if they found a priest they would cut off his head and sell it to the soldiers for five pounds. In St Mullins Churchyard there are the remains of a stone altar where the priests used to celebrate mass. If they heard the soldiers coming they would hide in a big hole called a vault. Here they would stay until the soldiers were gone, and then they would offer up the holy mass and give thanks to God for saving them from the priest hunters or soldiers.

Fairy forts

In this district there are many raths. There is one at the back of Powers of Templenabo. It has many palm trees growing in it. It is believed that in olden days small people, dressed in red clothes, used to march out every night after twelve oclock. Two black horses with chains bound round their legs and bodies. were seen running around it. Many people heard music and noise like churning inside. There was another rath in Ballybeg. It was in the only field the man had, and one year he sent a man to dig it. He went to the field. After a while the owner went out to see how his workman was getting on; he found him sitting in the field and nothing done. On the top of Temple-na-bo there is a rath in a field belonging to Ned Murphy Bahana. One night a man going home from playing cards, when near this rath heard music and when he was going his own lane he heard the banshee. In Poulmounty at John Brennan’s old barn behind a clump of furze and hawthorn there is a rath. This rath was covered over with rubbish and it is fenced off from the land. It is now full of rabbits. Many old people say that a man was out about snares and when he went over to the old rath he heard three loud cries. He looked and saw a strange creature close behind him. He ran home as fast as he could and when he reached home he was unable to speak. When the priest came he was unconscious and he died later. Mrs. Cleare, Ballywilliam >

Famine

In the years of 1846-47 the famine occurred. This was due to the potato crop getting rotten and the people had no food to eat. There were many people living round here at that time. The blight came one night but only rotted some of the potatoes Many people brought some of their potatoes into their barns and left the rest out in the field The blight came the second night and destroyed them all. During the famine the people had to eat grass for there was no other food in the county. It is said that women were found dead in the ditches with babies in their arms and bunches of grass in their mouths Numbers of people died during these two years due to the failure of the potato crop. John Behan, Poulmounty >

In the year of 1846 a man named Ned Murphy built a house in the wood near the giant stone. It was not long built when the famine came to Ireland and the first week of the plague was not too bad. After a month the potatoes were rotten and the crop failed. People had nothing to eat but the flesh of the animals When these were run out they had nothing people died in great numbers. A hundred people died between Borris and New Ross. There was no place to bury them They gathered them into the houses where the people were dead and threw the house on them. A plague followed From this disease my mother’s grandmother died. Stacia Cleare >

In the year 1846 and 1847. In the days of the famine people ate water-grass they were so hungry. Persons were found dead in the ditches for a bad sickness called cholera set in and thousands of people died of it. Thomas Doyle’s grandfather of Ballinaberna often related that he went to six funerals in the one house in a week. All died from that disease and no one was allowed within half a mile of the house. A famous drink called the Irish poteen was given to men to coffin them. The black potatoes and hunger caused this disease. Yellow meal was so dear and money so scarce that no one could afford to buy it. Thomas Doyle’s grandfather afterwards related that they had four loads of potatoes and had to store them upstairs so that they would not be stolen. Thank God we have better days now. >

St. Mullins during the famine years

Extracts from an article by Frank Clarke, published in Carloviana No. 45 (1997) >

Before dealing with the famine years as they affected the St. Mullins area, I think, perhaps, it would be worthwhile to have a brief look at the area in the years immediately prior to 1845 in order to get an idea of the state of the people and their lifestyles. Firstly, let’s look at the population of the Barony of St. Mullins as far as can be ascertained from the available records:-

1765 846

1800 3800

1821 4814

1831 5755

1841 5905

The enormous increase in the population from the year 1765 to the year 1800 of approximately 3000 was in line with the over-all increase for the country as a whole; it is estimated that the population of Ireland increased by four million people between 1780 and 1845 and that the increase between the years 1760 and 1815 was around 172 per cent.

Land Holdings

The farming community held their holdings either direct from the head landlords such as Thomas Kavanagh of Borris, the Earl of Courttown, Lord de Vesci and Robert Tighe or else from the middlemen. The rents payable to the principal land lords were generally in the region of 17/= to £1.50. The middlemen charged very much more; in the .townlands of Knockeen, for example, the middleman paid 1 Os/ 6d per acre and charged 45/= per acre to his undertenants. An additional burden on top of the rent charge was the price paid for lime. This cost some l/3d per barrel and was used at 30

barrels to the acre. From these various sources one can get a fair idea of the way of life in St. Mullins before 1845 – to summarise – the labourers and cottiers lived on the margins of society, well used to scarcity in most if not every year – depending on one crop – the potato – for sustenance and enduring extreme poverty for three to four months of every year.

The famine: The years 1845-1852

We now come to the famine years of 1845 to 1852 and perhaps a brief chronology of the period would be of help.

1845 – Blight came in September, most of the crop saved.

1846 – Relief Committees set up by Sir Robert Peel; complete destruction of potato crop.

1847 – Soup kitchens set up; worst winter in living memory; harvest small but good; Poor Relief Act enacted.

1848 – Potato crop failed again; cholera in towns.

1849 – Blight back again

In 1845 a Constabulary Report for County Carlow stated that the potato crop was a heavy one and that disaster was not felt throughout the county and that a large amount of the crop had been saved before the onset of the blight. In the Barony of St. Mullins the constabulary reported that the oats and barley crop were very good.

In November 1845 a Central Relief Committee was set up in Dublin to co-ordinate the relief measures throughout the country which were being handled by the Local Committees. In the St. Mullins area the chairman of the Relief Committee was the Reverend Daniel Maher, the Parish Priest at the time – the sec-

retuy being Jeremiah O’Keeffe of Marley. The policy of these Relief Committees was to provide employment so that labourers could buy food which had been the way previous relief schemes had been managed. Another objective was to ensure that local traders did not capitalise on the food scarcity by raising prices to an exorbitant level. This aim was to be achieved by ensuring that a reserve supply of cheap food was held in reserve and to this end Sir Robert Peel purchased Indian meal in America and had it stored in depots around the country, one of which was in Waterford.

It was decided at the end of 1846 to phase out the direct relief programmes and to replace them with direct outdoor relief and the model selected was the soup kitchen based on the methods used by the Society of Friends and others during the winter of 1846. There were delays in setting up these soup kitchens caused by problems in deciding who qualified for relief delays in making meal available at the kitchens and unfair conditions regarding the distribution of food.

Fr. Maher lashed out at those landlords and middlemen who did not subscribe or else gave very little, in the following terms. “We have appealed in vain to the landed proprietors —- the principal proprietor whose property in the district is worth seven thousand pounds a year, from him we could not get no more than £33. A lady residing in London who receives a rent charge of £500 a year from the Parish —- after a long delay we received £3.” Another £14 was sent by Sir Routh to the St. Mullins Committee in foot of this letter.

Two soup kitchens were set up in St. Mullins, one in Glynn village and the other in Marley in the Protestant school there. No records survive of the numbers relieved by these kitchens. The cost of these soups came out of local rates and hence the perceived need to make them as cheaply as possible. The last day that rations were distributed was August 28th 1847 and on that day 3,400 rations were issued in the Parish of St. Mullins.

When the Soup Kitchen Act ceased in August 1847 the only refuge left for the destitute poor was the New Ross Poorhouse – St. Mullins being in the New Ross Union This house had been built in 1842 to hold about 900 people. The stated principal of the poorhouse system was that it was to be as difficult as possible to get into – the conditions inside were to be worse than those prevailing on the outside – in other words it was a type of penal settlement and the master and those looking after the inmates were nearly always recruited from the ranks of the ex- military or ex-constables. The master was paid £40/50 a year, the matron got £35/40 and the clerk £60 – he had to deal with the voluminous correspondence that went back and forwards between the Houses and Dublin.

How did the famine years affect the St. Mullins area?

Firstly, there was a dramatic drop in population between the 1841 and 1851 Census Returns.

In 1841 the population of the Barony of St. Mullins was given as 7,640 and the Parish of St. Mullins as 5905. These figures had been reduced to 5,781 for the Barony and 4,486 for the Parish by 1851 – the reduced figures being due either to deaths from Famine, disease of emigration. The decrease shows up dramatically in the Parish Registers of St. Mullins when one compared pre famine births and marriages

to post famine figures. The average number of marriages per annum from 1840 to 1846 was 35 – this fell to 15 per annum for the seven years from 1847 to 1853 – a drop of some 57%. The marriage rate form 1853 to 1863 show a slight increase to 17 per annum and the figures for 1864 to 1871 show a drop to 14 per annum. The births for the Parish show an equally dramatic reduction. The average number of births for the seven years from 1840 to 1846 was 173 per annum – this fell to 90 per annum for the

years 1847 to 1853 – a decrease of some 48%. in the years form 1853 to 1863 the average yearly number of births was 73. Unfortunately the Parochial Register does not commence to show deaths until 1875 but it has been estimated that for the period 1835 I 1845 that there were 100 deaths to 175 live births approximately – this would give a rough figure of 1000 deaths for the period 1841 to 1851.

The school roll numbers highlight the drop in numbers in the Parish.

School 1846 1849

Finch 157 107

Glynn 319 176

Newtown 357 220

Drummond 226 169

At a rough estimate approximately 2000 left the Parish during the years 1841 to 1851 – either to emigrate overseas or elsewhere outside the Parish of St. Mullins. How did the Landlords in the Barony of St. Mullins react to the Famine period? Unfortunately the Rental Rolls for the Kavanagh seem to be extant only from 1853 onwards – these show very few evictions for the immediate post famine years. There does exist, however, the Rental Roll for the townland of Bahana where the present day Church and School in Glynn are situated – this covers the period from 1843 to 1851 and gives a glimpse of how the small farms, cottier and labourer were dealt with by a middle landlord during the famine years.

This townsland of Bahana had been held by the Rossitter family since circa 1780 and at the period we are concerned with was held by a Mrs. Cecelia Rossitter Byrne on a long lease form the head landlord, Thomas Kavanagh of Borris. In 1843 there was a total of 47 families living in Bahana and the adjoining townsland ofBandi – the size of the holdings were as follows. Labourers (no land) 6/10 acres 11/15 acres 16/30 acres Over 30 acres 7 15 7 5 4 The rents were from £80 per annum for holdings over 30 acres down to £2 to £3 for the smallest holdings of around 2 acres. By 1851 only 25 families were left in both these townslands and to go through the Rental Book makes for sad reading, showing how these land holders never seemed to be able to clear off their arrears of rent and perhaps, to these families, assisted emigration would have been the lesser of two evils.

Rental Book entries

Here are some instances of entries in the Rental Book for Bahana – each family had a page to itself detailing the acreage of the holding, the rent per acre and details of the arrears due form year to year.

“Patrick ___ had 8 acres; 1/2 year’s rent was £4-8-41/2. In 1847 his arrears amounted to £26 and at the bottom of the page is the stark word “gone”.

“Mrs. ____ , widow, had 6 acres; in 1843 her yearly rental was £9-10-0p; arrears in 1849 £27-0-0; last entry marked “gone to America”.

“Daniel ____ , 6 acres; in 1843 1/2 years rental was £4-19-8. in 1847 his arrears amounted £25-10-0 and the last entry has the observation “dead”. ( This man had eleven children).

It is noticeable that the bigger farmers were not treated the same way as the smaller ones when arrears accumulated. In one noticeable instance the biggest farmer in the area whose yearly rental was some £80 had arrears of £342-0-0 in 1851 but no action was taken against him, presumably because it was felt that his holding of some 50 acres was a viable one and that the arrears could eventually be cleared.

The 27 families marked in the rental book as “gone” or “emigrated to America”, amounted to some 130 persons, including 82 children which is almost exactly the difference in population between the years 1841 and 1851 for the townsland of Bahana. Another point worth highlighting is the fact that it was the neighbouring land holders who, in most cases, cleared off the arrears of their neighbours and took over the vacant plots, sometimes even at reduced rents and this was done without, it seems, any agitation on the part of anyone in the parish. This was not the case in the 1830’s and early 1840’s when anyone who took over even as small an amount as an acre from which someone had been expelled, was subjected to a barrage of threatening letters, burning of corn richs and the maiming or killing of cattle and sheep which could go on for two and three years at a time.

Emigration

Emigration form the St. Mullins area was through New Ross to either America or Canada and according to the New Ross Harbour Commissioners’ Records some 22 vessels went from New Ross to Quebec between 1848 and 1852 with emigrants. The number of persons on these vessels would have been some 2500. Waterford would also have been a place of emigration. Looking through the Parish and other Records it is interesting to see that from about 1840 to 1854/1855 whole families emigrated whereas after the mid 1850s it is very noticeable that single family members emigrated leaving the oldest son at home.

It is also noticeable that this eldest son would have to wait till the rest of his siblings were settled in life before he too could marry, with a reduction to family size compared to previous generations.

How did the St. Mullins area fare out compared to neighbouring areas during the famine years? From talking to the old people of the parish and from general folklore in the area it would seem that deaths from starvation were few and far between; that any deaths that did occur were due to famine fever so called. Of the 7,568 deaths in County Carlow between 1841 and 1851 fever accounted for 2,516 and consumption (T.B.) accounted for 2,138. The potato crop was not affected as much in County Carlow as

it was in the surrounding Counties.

Ship records: Emigration from St. Mullins to the USA c. 1850

Patrick Kennedy left New Ross 1849.

Boston seems the most likely port

Land records – Ballyknock

Voting records 1838

COUNTY OF CARLOW, REGISTERED OF VOTES, LAST DAY OF FEBRUARY, 1838. An Alphabetical List of persons who have Registered Votes pursuant to the Act of the 2nd and 3rd of William IV., chap. 88, to the lst day of February, 1838. BARONY OF ST. MULLINS >:

32 Murphy, Pierce Ballyknockvicar Ballyknockvicar £10 (Registered to vote:) 19 Oct 1836

Voting records 1840

[LISNAVAGH ARCHIVE, COURTESY OF LORD RATHDONNELL, VOTERS LIST FOR BARONY OF ST MULLINS, CO. CARLOW 1840 >]Michael Murphy Ballynockvicar £10 Registered 21 Oct. 1836

List of Recogizancers forfeited at Carlow Sessions 17th October 1822. [Purcell papers >]

Patt and Michael Doyle of Ballynockvicar, Parish and Barony of St Mollins, £10 each for not prosecuting Matthew Murphy, Charles Murphy,Patt Murphy and others.

James Doyle of Ballynockvicar, Parish and Barony of St Mollins, £40 for not appearing to answer such things as should be objected against him.

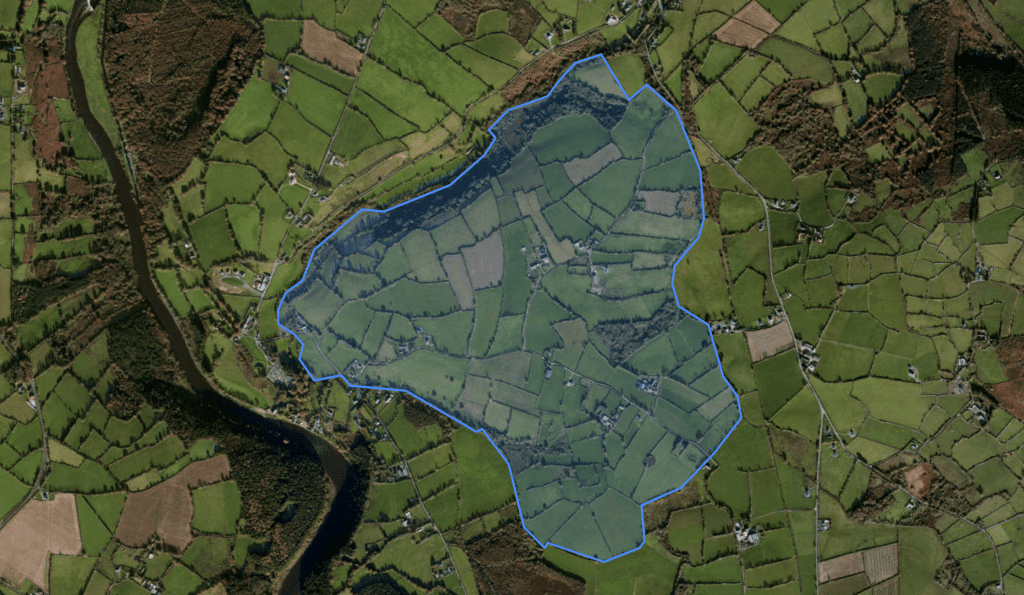

Ballyknock or Ballyknockvicar, townload boundary at https://www.logainm.ie/en/3576